Brazilian Dialogue

Land project gave dignity to the poor

I've just reread the 92-page report a research team released in 1987 detailing the Diocese of Maceio's land reform project at Cascuda.

A farm of some 1,200 acres was bequeathed to the archdiocese in 1916. But the diocese's administration of this "farm" with its 130 families differed not at all from that of the local owners, often called "colonels," though none of them belonged to the military.

These cane-raising owners were rapidly turning to cattle by 1970, expelling their workers, turning their poverty into destitution.

In 1974 Dom Miguel became Archbishop of Maceio. Here was an enlightened man, a man who understood that feudal policies of land holding did not jibe with the Gospel.

Rev. Sylvester Vredegoor seized the moment. With Dom Miguel's help, he wrested Cascuda from diocesan control plus the smaller property of Floresta.

Part of Cascuda's 1,200 acres were set aside for communitarian enterprises. The rest was allotted to the 130 families according to the size of their families.

But this was the easy part. Now the real fun began: a) how to deal with reactionary members of the clergy who wanted the properties back (eventually Floresta was retaken, its families given a cash payment to leave, and a padre then ran cattle on its acres. Cattle are much more malleable and profitable than people!); b) how to deal with neighbouring owners. One example of this intransigence: the folks of Cascuda were not permitted a one-kilometre shortcut to the highway, crossing a bit of pasture. Instead, they had to traverse "the road of 17 gates," a detour of many kilometres. It took years, court processes and much time and energy to get the government to expropriate the few meters' width needed for the shortcut access road; c) most difficult of all was how to create a community of these many families whose farmer society of dependence and exploitation was now swept away but who hadn't the formation needed to work together in democratic, co-operative fashion.

Dom Miguel asked Sylvester to assume this task, a task worthy of Hercules. And Sylvester -- idealistic, enthusiastic, but also impulsive -- assumed it with no holds barred.

So many crises, so many telephone calls, some coming in the middle of the night. And always he made the long journey roaring off on his motorcycle in emergencies, using the truck (well-stocked) in more planned trips.

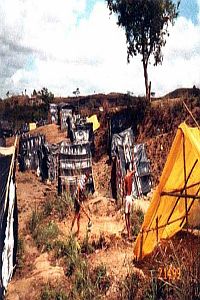

And did Cascuda flourish under his watch and counsel? Yes, if you can look at its accomplishments: a dam to avoid flooding and to have water in drought time; fish ponds; cisterns and dugouts; community orchards; a community flour mill; a three-room school; a community centre; the access road.

But, no, if you look for a society in which toleration, peaceful co-existence, all for one and one for all were the order of the day.

In short, Cascuda had the same mix of successes and failures that all our communities have, even here in Saskatchewan, the show-province of co-operatives.

But none can take from Sylvester the supreme accolade one of the community gave in a deposition to the research team: "Before this we were work-animals; now we are folks!"

Al Gerwing